Exploring the Trolley Problem: An Ethical Quandary

The Trolley Problem is one of the most famous thought experiments in ethics, posing a fundamental moral dilemma that has sparked intense debate among philosophers, ethicists, and students of moral philosophy. It’s a hypothetical scenario that forces individuals to confront the complexities of moral decision-making, particularly when it comes to questions of life, death, and the consequences of our choices.

In this article, we’ll delve into the Trolley Problem, explain its variations, and explore its significance in ethical theory, offering insights into how it challenges our understanding of morality, utilitarianism, deontology, and more.

What Is the Trolley Problem?

The Trolley Problem was first introduced by British philosopher Philippa Foot in 1967 and later expanded by Judith Jarvis Thomson. The problem revolves around a moral dilemma where a person must make a difficult decision to intervene in a life-or-death situation.

The classic version of the problem is as follows:

A runaway trolley is headed down a track toward five people who are tied to the track and cannot move. You’re standing next to a lever that can divert the trolley onto another track, where there is one person tied up. The dilemma you face is whether to pull the lever, diverting the trolley to the second track and killing one person, or do nothing, allowing the trolley to continue on its current path and kill five people.

This simple scenario forces a person to make a choice between saving more lives at the expense of one, or refraining from action and allowing a greater number of deaths to occur. The question posed is: What is the right thing to do?

The Ethical Dilemmas at Play

The Trolley Problem raises several ethical questions, which often revolve around moral principles such as utilitarianism, deontology, and the value of individual life. Let’s break down how these ethical frameworks approach the problem:

1. Utilitarianism: The Greater Good Approach

Utilitarianism, popularized by philosophers such as Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, advocates for maximizing happiness and minimizing suffering for the greatest number of people. From this perspective, the moral choice would be to pull the lever, diverting the trolley to the track with one person. The logic is straightforward: sacrificing one life to save five would result in a better overall outcome, as it minimizes the total amount of harm.

Utilitarianism hinges on the principle of consequentialism, meaning that the morality of an action is judged solely by its consequences. In the Trolley Problem, the action that produces the most favorable result for the largest number of people would be deemed the correct one.

2. Deontology: The Duty-Based Approach

In contrast to utilitarianism, deontology, as espoused by Immanuel Kant, focuses on the morality of actions themselves, rather than their consequences. According to deontological ethics, there are moral rules or duties that must be followed, regardless of the outcome. One such rule is the imperative not to kill, as it is considered an absolute moral duty.

A deontologist would argue that pulling the lever to intentionally cause one person’s death, even to save five others, is morally wrong because it violates the moral duty not to kill. From this perspective, refraining from action and allowing the trolley to continue on its path, though resulting in the deaths of five people, would be the morally acceptable choice because no direct action to kill is taken.

3. Virtue Ethics: Focusing on Character and Intentions

Virtue ethics, rooted in the philosophy of Aristotle, focuses on the development of good character traits rather than following specific rules or maximizing overall utility. In the context of the Trolley Problem, a virtue ethicist would likely consider the character and intentions behind the action.

If you pull the lever to save five people, virtue ethics would examine your motivation. Are you acting out of compassion and care for the greater good, or is it out of a sense of duty to avoid guilt? Alternatively, if you decide not to intervene, virtue ethics would consider whether you are showing courage, compassion, and respect for human life. The focus would be on your intentions and whether your actions reflect virtues like kindness, wisdom, and justice.

Variants of the Trolley Problem

Over time, the Trolley Problem has been modified to explore various nuances in ethical reasoning. Some of the most well-known variants include:

1. The Fat Man Variant

In this variation, instead of a lever, you are standing on a bridge overlooking the track. A large, heavy man is standing next to you, and you can push him onto the track to stop the trolley, saving the five people tied up. The question is similar: Do you sacrifice the one person (the fat man) to save the five others, even though doing so requires you to directly kill someone?

This version adds complexity, as many people feel intuitively that pushing the fat man is morally different from pulling a lever, even though the outcome is the same.

2. The Loop Variant

In the loop variant of the Trolley Problem, the tracks form a loop, and diverting the trolley onto the second track will cause the trolley to hit a person who is large enough to stop the trolley and save the five others. In this case, the person on the second track would be directly involved in stopping the trolley and preventing further harm. This variant challenges the intuition further, questioning whether it is ethically justifiable to use a person as a mere instrument for saving others.

3. The Transplant Variant

In this variant, a surgeon has five patients who need organ transplants to survive, but there is only one healthy donor who matches all five. The surgeon has the opportunity to kill the healthy donor and use their organs to save the five patients. This situation tests the limits of utilitarian reasoning in medical ethics, asking whether it is justified to sacrifice one life to save many, even if the action is morally repugnant.

Why the Trolley Problem Matters

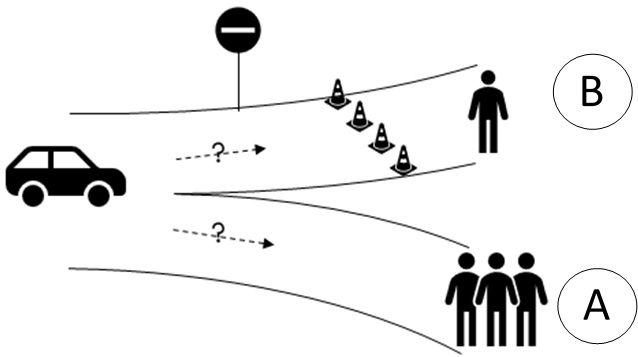

The Trolley Problem has significant value not just in philosophical debates but also in practical ethics. It forces us to examine the complexities of decision-making in high-stakes situations, such as medical ethics, self-driving cars, military strategy, and even criminal justice.

For example, self-driving cars may one day be faced with situations similar to the Trolley Problem, where the car must decide whether to swerve and hit a pedestrian to save the occupants inside, or to remain on course and potentially harm the passengers in the car. How we approach these decisions reflects not only our ethical priorities but also the kind of society we want to live in.

Conclusion: The Trolley Problem and the Complexity of Ethics

The Trolley Problem remains a compelling and challenging moral dilemma that tests the principles behind our ethical decisions. While it doesn’t offer simple answers, it offers valuable insights into how we think about morality, the consequences of our actions, and the complex relationship between intention, action, and outcome. Whether we choose to save more lives by acting decisively or decide that certain actions should never be taken, the Trolley Problem forces us to confront fundamental ethical questions that continue to shape our philosophical understanding and real-world decisions.

By examining the Trolley Problem, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complexities of ethical decision-making, as well as the limitations of any single ethical framework in answering tough moral questions. Ultimately, understanding these philosophical quandaries equips us to navigate the ethical challenges we encounter in our everyday lives and society at large.